This story published July 5,

1996

This story was updated January 15, 1997

From

the Supreme Teachings of Nazi Ideology

to the Ramifications

of Unprecedented Betrayal

by

Ursula Grosser-Dixon

It was 1942. In our high school in

Berlin-Spandau during the height of the second world war, a teacher

stood before us, dissecting separate phrases from Hitler's book "Mein

Kampf."Many sections of the book were hard to grasp for a teenage girl

of 13. Our teacher would wave his baton, pointing towards a sentence

scribbled on the blackboard which had made a particular impression on

the pedagogic mind.

It was 1942. In our high school in

Berlin-Spandau during the height of the second world war, a teacher

stood before us, dissecting separate phrases from Hitler's book "Mein

Kampf."Many sections of the book were hard to grasp for a teenage girl

of 13. Our teacher would wave his baton, pointing towards a sentence

scribbled on the blackboard which had made a particular impression on

the pedagogic mind.

Soon, we, being young and eager, began to absorb even the most

difficult passages most willingly. To the left of the classroom in

front of us stood a separate blackboard on a portable easel-like stand.

On it was written in boldly printed letters: WER HATTE RECHT? ICH HATTE

RECHT! (Who was right? I was right! ). We learned that we, the

privileged were the first generation to undergo the transformation from

every-day children into the magnificent exulted master race, which was

to last at least a thousand years. Very soon the atmosphere in the

classroom became that of fascination. Our ideas of the greatness of

this man called Adolf Hitler did lie perhaps in what we were told. In

the beginning of the movement, back in the 20's in Munich, Hitler was

considered a dreamer, a builder of castles in the sky. There were even

those who had called him crazy, but only a few years later all his

aspirations had become reality. We had to learn that he never wavered

from his chosen path. Often he had asked his associates: "Who was

right? Was it the man who had a clear vision of the future or was it

all the others? No, it was I who was right."

He was

many things to us; he was Frederick

the Great, Napoleon and Marx all rolled in one. It made a

great impression on the young mind that he had been his own teacher,

the creator of a powerful political party. He was someone who had

elevated himself from his insignificant beginnings in Braunau in

Austria by his own efforts. To us he was the great statesman, the

leader of men and the greatest tactician directing his armies on the

battlefields. But when he stood before us on the first day of May in

the Berlin Olympic Stadium to celebrate Labor day, he looked humble in

his plain uniform. He just stood there, seemingly transfixed by the

jubilation's of the people. He had the uncanny ability to present

himself to us as an instrument of providence. No one who had heard him

that day was left in doubt: before us had stood the Messiah.

I believe that few people today could understand what it meant to an

innocent young mind to be taken to such emotional heights, and then to

the utter disbelief and total desperation of finding out about the

death camps. I was unable to cope with this knowledge of horror in

1945. My whole being had been shattered by betrayal. Now, at the age of

16, I found myself like many of my class mates, unable to absorb barely

anything in school. The new teachings of democracy promoted feelings of

disgust towards all political factions. I

just skimmed by on the grades I made. It seemed as if I was trapped in

a black hole from which I could not free myself. Dr. Freud would

probably say it presented the state of mind, the total disbelief and

constant desperation which had severely traumatized me.

I turned away from my plan of becoming a teacher.

Very slowly I rotated to a new beginning. The only path open to me,

that would help to heal my soul, was the path that took me after high

school graduation to the only Jewish Hospital in West Berlin. I

enrolled in nursing school and I lived in a Jewish nurses residence

with Jewish room mates. My only chance for emotional stability laid

within the fact that somehow I had to get closer to the Jewish people.

I was angry with my own God who had in my narrow analysis let all this

happen: Six million innocent people. The depth of my despair took me to

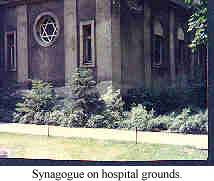

the God of the Jewish people. On the premises of hospital is a small

synagogue. There I sat often in the evening when no one else was

around, searching for answers I would never find.

I turned away from my plan of becoming a teacher.

Very slowly I rotated to a new beginning. The only path open to me,

that would help to heal my soul, was the path that took me after high

school graduation to the only Jewish Hospital in West Berlin. I

enrolled in nursing school and I lived in a Jewish nurses residence

with Jewish room mates. My only chance for emotional stability laid

within the fact that somehow I had to get closer to the Jewish people.

I was angry with my own God who had in my narrow analysis let all this

happen: Six million innocent people. The depth of my despair took me to

the God of the Jewish people. On the premises of hospital is a small

synagogue. There I sat often in the evening when no one else was

around, searching for answers I would never find.

The attitude of the Jewish staff towards us was

admirable. We were in fact accepted entirely on our own merits as human

beings. On a warm summer evening in 1951 my room mates and I were

getting ready to go to a dance at Resi Berlin. One of the girls, Ruth

Juliusburger, stood in front of the mirror with a long sleeved dress. I

asked her if she did not have anything cooler to wear. She turned

towards me, rolled up her sleeve and said in a very light voice "I

really don't want anybody to see my serial number!" ( For months I had

lived in the same room with her, but not once had I seen this mark of

disgrace. The explanation lies most likely in the fact that we always

wore long sleeved uniforms and it would have been totally out of

character for even one of the girls to say "here, look at this.")

The attitude of the Jewish staff towards us was

admirable. We were in fact accepted entirely on our own merits as human

beings. On a warm summer evening in 1951 my room mates and I were

getting ready to go to a dance at Resi Berlin. One of the girls, Ruth

Juliusburger, stood in front of the mirror with a long sleeved dress. I

asked her if she did not have anything cooler to wear. She turned

towards me, rolled up her sleeve and said in a very light voice "I

really don't want anybody to see my serial number!" ( For months I had

lived in the same room with her, but not once had I seen this mark of

disgrace. The explanation lies most likely in the fact that we always

wore long sleeved uniforms and it would have been totally out of

character for even one of the girls to say "here, look at this.")

That evening in our room in the residence, I just stood there, numb.

When Ruth saw the tears that had sprung from my eyes, she asked me in a

perfectly calm voice "Tell me, could you have done something? I don't

think so." A few minutes later she tried to calm me with five little

words: " Es war nicht Deine Schuld." (It was not your

fault.) Needless to say, I did not enjoy myself very much that night at

the dance. My friends certainly made every effort for all of us to have

a little fun. I pretended to enjoy myself, but deep inside of me all

that old desperation had once again come to the surface. That same

summer an incident occurred which brought me face to face with the

remnants of Nazi horror. On the grounds of the hospital was a smaller

building with a chronic facility. No non-Jewish staff worked there, and

we were of course curious. It was vacation time, and all wards were

short-handed. I received a call one day, asking me to come to this

chronic ward and lend a hand. There, the nurse on duty asked me to help

with a patient who had to be turned every hour. Entering the room I saw

a human skeleton in bed, a skeleton with layers of skin which kept the

organs from protruding. As I stood there, foolishly staring, I heard

this little high-pitched voice asking me "Sind Sie Jüdisch?" (

Are you Jewish? ) And I, quickly denying, not seeing the nurse who

gestured at me to agree, heard the worst accusations anyone could ever

hear "Get away from me, you murderer, you Nazi swine, you.... " I did

not hear more, I just ran and ran. I did not stop until I reached the

large bathroom at the end of the hall on the third floor residence,

having passed right by our room. I opened the window and sat on the

wide wooden ledge, looking down at the trees. A few minutes later I

heard Dr. Rosenberg, the Chief of Staff, speaking softly, persuading me

to come down with him for a cup of coffee. (The nurse at the chronic

ward had called him immediately after this incident, because she was

concerned about my state of mind.)

Walking downstairs with Dr. Rosenberg, his arm draped around my

shoulder, I started to get a hold of myself. In the cafeteria on the

first floor of the residence we sat for awhile without talking.

Suddenly he startled me by talking about the beauty of Venice, which

everybody should see at least once in their lifetime. Trying to follow

what he was saying, it came to me instinctively. All of a sudden I

understood his words: to forget the ugliness we can not change, to

remember the beauty still left in this world for us, if not for so many

others, it is there for us......

It was on this day that I started to live again, at least a little.

After graduating from the nursing school of the

Jewish hospital in Berlin-Reinickendorf, Iranische Str.2-4 in April '52

as a Registered Nurse in the Bundesrepublic of Germany, I worked at the

hospital for a year and a half. By now the Cold War was in full swing

and we were right in the center of yet another international conflict.

It forced me to assess my future in this unstable and highly explosive

situation, which eventually led to a decision. On October 15, 1953 I

left my homeland for a peaceful place called Canada. I went alone,

leaving behind my family, my friends, the Berlin where I had spent an

early carefree childhood, my language and my culture. Although the

twelve short years of the insanity of Nazi dictatorship had reeked so

much havoc and left scars that probably will never really heal, there

is so much more to Germany. It is also the land of Beethoven, Bach,

Brahms, Schiller, Goethe and so many more, who have contributed over

the years to its rich culture. It is also a country where people learn

trades and where people like to work. There are many economical and

social problems since re-unification, which took place on Oct. 3, 1990,

but I am confident that the people will again learn to live together,

after having been torn asunder for 29 years. I took part in the

glorious celebrations on October the third. Nobody expected this unification to happen in our

lifetime.

After graduating from the nursing school of the

Jewish hospital in Berlin-Reinickendorf, Iranische Str.2-4 in April '52

as a Registered Nurse in the Bundesrepublic of Germany, I worked at the

hospital for a year and a half. By now the Cold War was in full swing

and we were right in the center of yet another international conflict.

It forced me to assess my future in this unstable and highly explosive

situation, which eventually led to a decision. On October 15, 1953 I

left my homeland for a peaceful place called Canada. I went alone,

leaving behind my family, my friends, the Berlin where I had spent an

early carefree childhood, my language and my culture. Although the

twelve short years of the insanity of Nazi dictatorship had reeked so

much havoc and left scars that probably will never really heal, there

is so much more to Germany. It is also the land of Beethoven, Bach,

Brahms, Schiller, Goethe and so many more, who have contributed over

the years to its rich culture. It is also a country where people learn

trades and where people like to work. There are many economical and

social problems since re-unification, which took place on Oct. 3, 1990,

but I am confident that the people will again learn to live together,

after having been torn asunder for 29 years. I took part in the

glorious celebrations on October the third. Nobody expected this unification to happen in our

lifetime.

I was

asked a couple days later what I wanted to see first of the former East

Germany, where we now could drive freely. My wish was fulfilled. My

cousin Gisela and her friend Dora took me to Oranienburg, a place on

the northern outskirts of the city. There we visited the former

Concentration Camp Sachsenhausen. It covers a vast area, and walking

for hours through the former camp was an experience I shall never

forget. We took pictures that day and looking at them now, one can see

the anguish in our eyes.

I was

asked a couple days later what I wanted to see first of the former East

Germany, where we now could drive freely. My wish was fulfilled. My

cousin Gisela and her friend Dora took me to Oranienburg, a place on

the northern outskirts of the city. There we visited the former

Concentration Camp Sachsenhausen. It covers a vast area, and walking

for hours through the former camp was an experience I shall never

forget. We took pictures that day and looking at them now, one can see

the anguish in our eyes.

I keep myself informed

about my homeland through many visits and through the daily News

programs of the Deutsche Welle, which brings us TV Berlin via

Satellite. In my opinion the people are making a truly honest effort to

live in a peaceful united Europe. It took me decades to come to terms

with the horrible past, and I for one believe that we should never

forget all these innocent victims. But lately I have been deeply hurt

by a newly published book, written by an author who was not even born

then. He is telling the world at large that all ordinary Germans were

deeply complicit in the holocaust. People publish books to make money

and I respect their enterprises. But to say that we were all Hitler's

willing executioners, is not only completely false, it is an assumption

I deeply resent. I was there. I lived through it all. I know the truth

about the ordinary Germans, such as my family and my family's friends.

I have lost relatives in Stalingrad, Casino and in sea battles in the

Atlantic, all of them ordinary men drafted into the services to fight

for their country. One of my mother's aunts and her husband were blown

to pieces during an air raid on Berlin-Spandau. They were both in their

early 70's. They were decent people and really quite ordinary.

We barely escaped with our lives when our house was destroyed during

the Last Battle in 1945 and we did not know where my sister Irma was.

She had been arrested in July 1944 at the Radio Station where she had

worked in the cafeteria. She had foolishly circulated a printed joke

about Hitler among the employees and was tried for treason along with

several others at the people's court under Chief Justice Roland

Freisler. I thought at the time that such an action of circulating

inflammatory material was indeed very careless, when SS soldiers were

strutting about the communication center of Radio Berlin in

Charlottenburg. To this day I think it was careless. My mother could

have been spared all this grief, not to mention Irma herself. She

returned to us in August 1945 from a liberated camp in Poland. She

found us in a strange house in Staaken, which my uncle had found for

us. We had scribbled our new whereabouts on the ruin of our house in

Spandau. A few years later she opened a restaurant in Charlottenburg

with her friend, opera singer Martha Musial. Irma died last year, and

she too was an ordinary German who now stands accused, an ordinary

German who grew up without knowing her father who was killed in Russia

in WW I and lies somewhere in an unmarked grave since 1915. Sender

Freies Berlin published a booklet about the resistance at Radio Berlin:

"DARAUF KAM DIE GESTAPO NICHT." ("This didn't occur to the Gestapo.")

Presumably because the SS had the place covered. This booklet is very

interesting, because not many such transcripts from Nazi trials have

survived. It is free of charge and can be obtained by writing to:

Sender Freies Berlin (SFB)

Presse und Informationsstelle

Masurenallee 8-14

Berlin 14057

Germany

I was truly surprised when I read this booklet about 10 years ago. Irma

had never talked about her experience in prison or the trial. What

struck me were the deadly repercussions that circulating this material

at the Radio Station had. Of the nine people charged with treason,

three received a death sentence. My sister Irmgard Barich was sentenced

to 7 years without honor to a penitentiary. Later I found out she had

been at the Women's Penitentiary in Jauer (which most likely has a

Polish name today) and from there they were taken to a camp in Poland,

as the front lines were getting ever closer.

Life was hard for many people. So hard in fact, that one man who

returned in '47 from a POW Camp in Russia told me that the ones who did

not survive were the lucky ones. He too was an ordinary German and an

ordinary soldier who had fought for his country and lost. History tells

us that after any armed conflict the

victor is the one who is always right. I would like to mention a book

here which is very enlightening and astonishingly frank. It is called

"Meeting of Generals." Tony Foster is the author and it was published

in 1986 by Methuen Publications in Agincourt, Ontario.

Yes, there were many fanatical people in my country during WW II. There

were many who wore their party badge proudly and there were those, as

we now know, who willfully participated in the destruction of human

beings. Perhaps it is my great fortune that I never met any of them. We

had known about the re-locations, nobody made a secret of it. However,

I believe that the culprits in the death camps were sworn to secrecy

and there most likely were some people who did know and looked the

other way. In wartime Berlin, as elsewhere in the German occupied

territories, people had one goal in common: to survive this terrible

time. The German people as a whole were kept in ignorance, especially

the young, because the regime could not afford to shatter the myth. One

example: we were all blinded by tears at Rommel's funeral in the fall

of 1944, where hundreds of boys and girls had been brought in from all

over the country to help with crowd control. We cried because our hero

had succumbed to his wounds he had sustained when his car overturned

after it had been fired on by Allied planes. Yes, the government of the

Third Reich gave our hero an elaborate state funeral. However, the

government did not tell us what we now know: Rommel was forced to

commit suicide by taking poison because he was implicated in the plot

to kill Hitler on July 20, 1944.

Now, I asked myself a question: Why were we not told the truth? I think

I now know the answer. Appearances had to be kept up at all costs so

that we, the young people, did not become disillusioned. I can assure

every reader, that if the papers would have written that thousands and

more thousands of people from many nations were being destroyed, as

well as the whole Jewish race being eradicated and their remains, after

first being gassed, thrown into incinerators, there would have been

such a disillusioning, that I can not even imagine the reaction of my

classmates and all the young people I knew. Remember, we were the ones

who were to carry the torch and banners of honor into the future. We

were the ones who were chosen to act out Hitler's fantasy of a pure and

proud master race. No. We were faithful to the bitter end, because we

believed in him.

And we were bitterly betrayed.

Before I come to the end of this story, I would like to mention

something which has bothered me over the years every time I read

history books about World War II. I see words such as Nazi soldier,

Nazi Navy, Nazi this or that. I would like to clarify that Nazi is an

abbreviation for National-Socialist Party, a political party with

voluntary membership. Not one person in my own family was a party

member, and neither were the bulk of the armed services who fought in

the Wehrmacht, the sailors on the ships or the airmen of the Luftwaffe.

It is customary now to refer to my homeland during this awful conflict

as Nazi Germany because the government of the Third Reich consisted of

members of this political party. The founder of this party was a

dictator and in charge of the country. This, however, did not make

every fighting soldier on the different fronts a Nazi. There were, of

course, specialized SS Tank divisions, etc., whose soldiers were most

likely all party members.

The same holds true for

the Russian Army. Just because a dictator named Stalin was a dyed-in

the-wool communist, it didn't make every Russian soldier who fought so

gallantly for his motherland a member of the Communist party. During

the Cold War hateful sentiments were vented by calling the Russian

soldiers dirty Commies and Reds. We called the soldiers, who fought for

the United States under FDR and Truman, American soldiers, not

Democrats, although the democratic party was in power from 1933-1945.

Perhaps my reasoning makes little sense, perhaps it is painfully naive,

but somehow it seems wrong to me to call every enlisted service man in

Germany during WW2 a Nazi soldier.

This is a

completely honest account. The reader can draw his or her own

conclusion, whether or not all German people should stand accused of

all these unspeakable crimes committed during the years of utter

insanity in the name of the Führer Adolf Hitler.

This article was written by

Ursula Grosser Dixon, a novice historian. To read more of her stories,

visit Ursula's History Web.

Click here

to send her your comments or questions.

It was 1942. In our high school in

Berlin-Spandau during the height of the second world war, a teacher

stood before us, dissecting separate phrases from Hitler's book "Mein

Kampf."Many sections of the book were hard to grasp for a teenage girl

of 13. Our teacher would wave his baton, pointing towards a sentence

scribbled on the blackboard which had made a particular impression on

the pedagogic mind.

It was 1942. In our high school in

Berlin-Spandau during the height of the second world war, a teacher

stood before us, dissecting separate phrases from Hitler's book "Mein

Kampf."Many sections of the book were hard to grasp for a teenage girl

of 13. Our teacher would wave his baton, pointing towards a sentence

scribbled on the blackboard which had made a particular impression on

the pedagogic mind. I turned away from my plan of becoming a teacher.

Very slowly I rotated to a new beginning. The only path open to me,

that would help to heal my soul, was the path that took me after high

school graduation to the only Jewish Hospital in West Berlin. I

enrolled in nursing school and I lived in a Jewish nurses residence

with Jewish room mates. My only chance for emotional stability laid

within the fact that somehow I had to get closer to the Jewish people.

I was angry with my own God who had in my narrow analysis let all this

happen: Six million innocent people. The depth of my despair took me to

the God of the Jewish people. On the premises of hospital is a small

synagogue. There I sat often in the evening when no one else was

around, searching for answers I would never find.

I turned away from my plan of becoming a teacher.

Very slowly I rotated to a new beginning. The only path open to me,

that would help to heal my soul, was the path that took me after high

school graduation to the only Jewish Hospital in West Berlin. I

enrolled in nursing school and I lived in a Jewish nurses residence

with Jewish room mates. My only chance for emotional stability laid

within the fact that somehow I had to get closer to the Jewish people.

I was angry with my own God who had in my narrow analysis let all this

happen: Six million innocent people. The depth of my despair took me to

the God of the Jewish people. On the premises of hospital is a small

synagogue. There I sat often in the evening when no one else was

around, searching for answers I would never find. The attitude of the Jewish staff towards us was

admirable. We were in fact accepted entirely on our own merits as human

beings. On a warm summer evening in 1951 my room mates and I were

getting ready to go to a dance at Resi Berlin. One of the girls, Ruth

Juliusburger, stood in front of the mirror with a long sleeved dress. I

asked her if she did not have anything cooler to wear. She turned

towards me, rolled up her sleeve and said in a very light voice "I

really don't want anybody to see my serial number!" ( For months I had

lived in the same room with her, but not once had I seen this mark of

disgrace. The explanation lies most likely in the fact that we always

wore long sleeved uniforms and it would have been totally out of

character for even one of the girls to say "here, look at this.")

The attitude of the Jewish staff towards us was

admirable. We were in fact accepted entirely on our own merits as human

beings. On a warm summer evening in 1951 my room mates and I were

getting ready to go to a dance at Resi Berlin. One of the girls, Ruth

Juliusburger, stood in front of the mirror with a long sleeved dress. I

asked her if she did not have anything cooler to wear. She turned

towards me, rolled up her sleeve and said in a very light voice "I

really don't want anybody to see my serial number!" ( For months I had

lived in the same room with her, but not once had I seen this mark of

disgrace. The explanation lies most likely in the fact that we always

wore long sleeved uniforms and it would have been totally out of

character for even one of the girls to say "here, look at this.") After graduating from the nursing school of the

Jewish hospital in Berlin-Reinickendorf, Iranische Str.2-4 in April '52

as a Registered Nurse in the Bundesrepublic of Germany, I worked at the

hospital for a year and a half. By now the Cold War was in full swing

and we were right in the center of yet another international conflict.

It forced me to assess my future in this unstable and highly explosive

situation, which eventually led to a decision. On October 15, 1953 I

left my homeland for a peaceful place called Canada. I went alone,

leaving behind my family, my friends, the Berlin where I had spent an

early carefree childhood, my language and my culture. Although the

twelve short years of the insanity of Nazi dictatorship had reeked so

much havoc and left scars that probably will never really heal, there

is so much more to Germany. It is also the land of Beethoven, Bach,

Brahms, Schiller, Goethe and so many more, who have contributed over

the years to its rich culture. It is also a country where people learn

trades and where people like to work. There are many economical and

social problems since re-unification, which took place on Oct. 3, 1990,

but I am confident that the people will again learn to live together,

after having been torn asunder for 29 years. I took part in the

glorious celebrations on October the third. Nobody expected this

After graduating from the nursing school of the

Jewish hospital in Berlin-Reinickendorf, Iranische Str.2-4 in April '52

as a Registered Nurse in the Bundesrepublic of Germany, I worked at the

hospital for a year and a half. By now the Cold War was in full swing

and we were right in the center of yet another international conflict.

It forced me to assess my future in this unstable and highly explosive

situation, which eventually led to a decision. On October 15, 1953 I

left my homeland for a peaceful place called Canada. I went alone,

leaving behind my family, my friends, the Berlin where I had spent an

early carefree childhood, my language and my culture. Although the

twelve short years of the insanity of Nazi dictatorship had reeked so

much havoc and left scars that probably will never really heal, there

is so much more to Germany. It is also the land of Beethoven, Bach,

Brahms, Schiller, Goethe and so many more, who have contributed over

the years to its rich culture. It is also a country where people learn

trades and where people like to work. There are many economical and

social problems since re-unification, which took place on Oct. 3, 1990,

but I am confident that the people will again learn to live together,

after having been torn asunder for 29 years. I took part in the

glorious celebrations on October the third. Nobody expected this  I was

asked a couple days later what I wanted to see first of the former East

Germany, where we now could drive freely. My wish was fulfilled. My

cousin Gisela and her friend Dora took me to Oranienburg, a place on

the northern outskirts of the city. There we visited the former

Concentration Camp Sachsenhausen. It covers a vast area, and walking

for hours through the former camp was an experience I shall never

forget. We took pictures that day and looking at them now, one can see

the anguish in our eyes.

I was

asked a couple days later what I wanted to see first of the former East

Germany, where we now could drive freely. My wish was fulfilled. My

cousin Gisela and her friend Dora took me to Oranienburg, a place on

the northern outskirts of the city. There we visited the former

Concentration Camp Sachsenhausen. It covers a vast area, and walking

for hours through the former camp was an experience I shall never

forget. We took pictures that day and looking at them now, one can see

the anguish in our eyes.